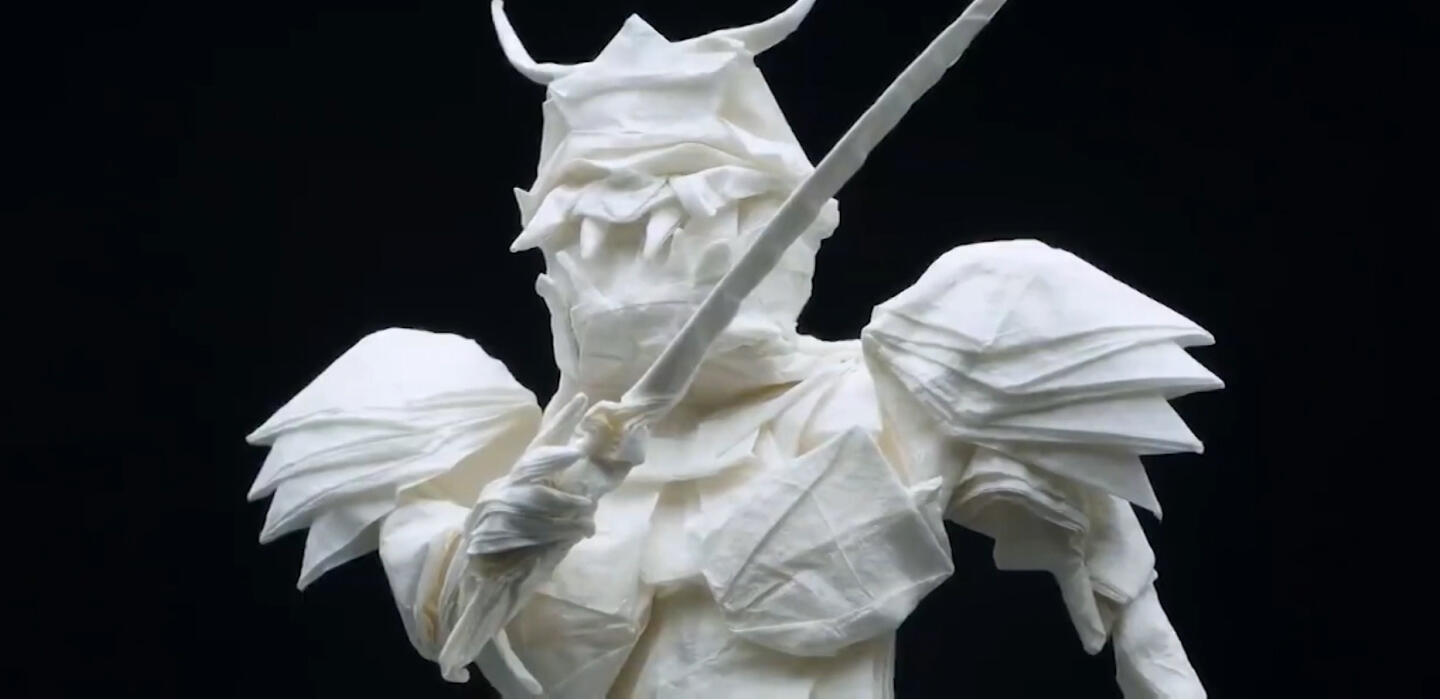

這一個細細的日本武士手辦在網上社交平台大受注視。它只有28厘米高,身體每一個部分都是用紙張造成,創作它的人是一位芬蘭藝術家 Juho。Juho 畢業於芬蘭拉普蘭大學,學校的位置十分接近瑞典與北極圈的邊境。手辦用一張95厘米長的正方型紙張製成,Juho小心翼翼,預先在紙上做出縱橫交錯的摺痕,然後一邊用手摺疊一邊塗上清水。弄乾之後,四肢、身軀慢慢成型,連手指都可以雕造出來。

整個製作過程用上了足足50小時,但巧妙之處是 Juho 從沒有剪開或者撕破紙張,亦不用任何工具,靠的只是技巧和自己一雙手,當然還要有非常豐富的想像力。我們看到的是一位芬蘭人用日本武士作為他創作的原型,但材料呢?

原來是來自中國。中國溫州被山、海和436個小島環繞,在歷史上是一個著名的港口。很多居住在意大利的中國僑民祖先都來自這裡,亦是一個沿海的開放城市,貿易興盛。當地還出產傳統的溫州皮紙,成為 Juho 今次大作的材料,在網購平台亞馬遜和美術用品公司都可以買到。大卷小卷的溫州皮紙,還有吸水力強弱和不同重量厚薄之分,自古以來無數水墨畫作同名句都寫在溫州皮紙之上。

中國的摺紙技藝源遠流長,最初是用在其他的物料上。歷史的記載甚至比起造紙工藝更早出現,後來的發展應用得越來越廣泛。到今天,一般家庭用的祭祖物品都有部分用紙摺成。溫州皮紙非常輕巧,紙質較韌,因此可以成為很多像 Juho 一樣的藝術家選用的材料。中國與造紙技術是兩個分不開的名字,其歷史可以追溯到 公元25年至220年的東漢。造紙的工藝一代傳一代,影響十分深遠,文學得以由手抄本開始一直發展至今,以各種各樣的模式與我們的生活接軌。

就像其他偉大的發明一樣,造紙技巧一路沿著海上絲綢之路傳揚,東南亞、印度、中東地區、歐洲大陸還有美洲。傳統的中國造紙工藝十分講究,有造漿、烘乾、剪裁。工匠精神由老師父傳授,新學藝的人要花上3年時間才可以造出跟前人製作水準相若的紙張。有色澤、耐用而且上墨容易的溫州皮紙,一張承載了千年文化智慧的紙張,還有Juho 無邊的創造力,造就了以上這一個不同文化交錯的美麗成果。

Meet the man of the moment on social media, a paper samurai standing 28 cm tall. It was made by Juho Könkkölä, an art graduate from the Lapland University of Applied Sciences in Finland, not far from the border with Sweden and the Arctic Circle.

From a single sheet of paper measuring 95 by 95 cm, Juho pre-creases the material and collapses it into human form, then by applying water is able to form intricate details such as the hands and fingers, fixing its final shape by drying it into place. There are no cuts and no tears in this 50-hour process and no tools other than his hands, his skill and his imagination.

But while the artist is from Finland and the subject is Japanese, the paper he uses is from China. Wenzhou is a city surrounded by mountains, sea and 436 islands. Historically, it was known for its port and more recently has earned a reputation as a leading center of commerce and for being the ancestral home of most of the overseas Chinese in Italy today. But it also gives its name to the Wenzhou rice paper that Juho uses to create his expressive works.

On Amazon and in art supply shops, you can find rolls of this thin sheet material in different dimensions and weights, acid-free and absorbent. And it can also be used for ink-and-brush works from painting to calligraphy. Folding in China can be documented so far back that it pre-dates the invention of paper and was likely first-used as a technique on other materials.

Later, it became a central part to Chinese families when traditional funerals, still in practise today, used paper folding to represent gold nuggets and other objects that the deceased would take into their afterlife.

The rice paper in its early forms was durable yet dexterous and explains why artists like Juho still use it today. Paper is embedded in the Chinese soul. The first papermaking process was recorded during the Eastern Han, a period from 25-220 AD.

Its impact was so deep, accelerating the written culture in China and in turn the reading culture we enjoy today from manuscripts to e-books. And of course, paper traveled to different regions including East Asia, the Islamic centers, the Indian subcontinent, Europe and the New World.

But the complex techniques involving pulp, drying and cutting continues to draw on the long lineage of craftspeople who came before us. Even now, craftsmen can take three years to produce quality paper that’s as strong, durable and ink-absorbent as their ancestors were able to achieve. Rice paper is a testament to that creativity and as Juho’s story shows, it also speaks to the beauty of interconnected cultures in an interconnected world.